Update: March 25, 2015, see also: Certificate transparency on blockchains

Ben Laurie, project lead for Google’s Certificate Transparency (CT), recently published an article wherein he compared CT against various efforts to secure Internet communication world-wide from Man-In-The-Middle Attacks (MITM), including DNSChain.

In it, he made several claims about CT and related topics:

- That CT leads to a situation where "It becomes impossible to misissue a certificate without detection"

- That no one has come up with a way to "effectively revoke self-signed certificates"

- That CT is a "Generally applicable" system where "No one is special" and where everyone "[is] able to participate"

- That CT doesn't introduce trusted third-parties

- That CT doesn't push decisions onto the end user

- That DNSChain wastes energy and "has no mechanism for verification"

And yet, decisions that impact the security of the entire Internet are being made based on these statements. We (the Internet community) need more eyeballs and brains on this.

In this post, I will:

- Give a summary of what Certificate Transparency is

- Explain why Certificate Transparency does not live up to its name

- Respond to Laurie's criticism of DNSChain, Bitcoin, and blockchain systems in general

Summary of Certificate Transparency

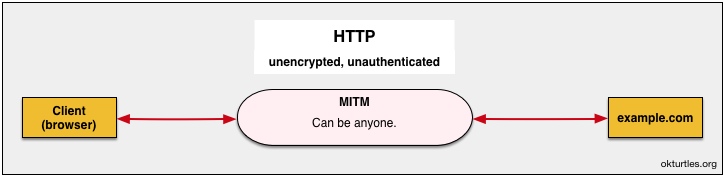

To understand CT, one must first understand what a MITM attack is, and how HTTPS connections are "secured" from MITM attacks today:- Watch first: our brief animated explanation of HTTPS MITM attacks

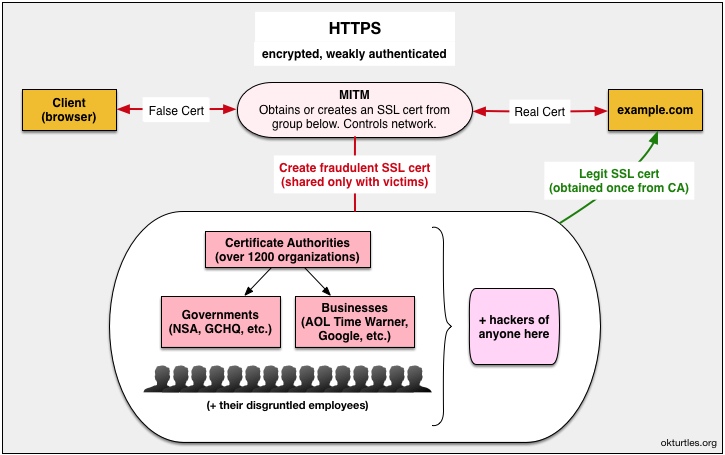

The diagram below shows how many MITM attacks circumvent HTTPS today. This is explained in more detail in the video linked to above.

Currently, CT does not attempt to prevent these attacks from happening.

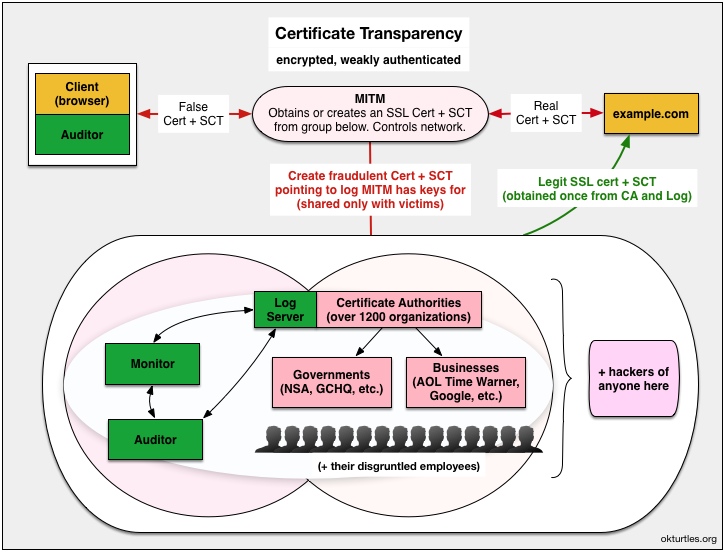

Instead, it attempts to make these attacks easier to detect after they’ve successfully happened, but as we’ll see, it doesn’t even guarantee that. At its core, it introduces the concept of an append-only auditable log that is guaranteed to show the most recently issued SSL cert for any given domain (IF you’re able to ask it). EDIT September 27, 2014: Actually, that is not true. Auditors are not shown the most recent cert for any arbitrary domain. Verifying that no fraudulent certificates have been issued by a rogue CA is the responsibility of Monitors, who continuously poll logs and download their contents.

Websites that want to run HTTPS purchase (annually) an SSL certificate from a Certificate Authorities (CAs). In CT, the CA takes the additional step of informing log(s) about this new certificate. The website owner can independently check the logs to confirm his certificate is there. His server will then attempt to send this certificate to all visitors.

The problem, however, is that not everyone will see this certificate.

If you’re able to, take a moment to go read Google’s documentation on how CT is supposed to work. Pay close attention to the four figures that they currently have there (except the one on OCSP stapling; it’s not relevant to the overall security of the system). Here’s a copy of that page. When you’re done, return here.

Back? OK.

Let’s dive into the claims Google is making.

Google's inaccurate claims about Certificate Transparency

#1: CT makes it "impossible to misissue a certificate without detection."

First, note that Laurie's new claim stands at odds with his own RFC, which states that it is the responsibility of domain owners to remain vigilant and check the logs. If no one checks, clearly it will go undetected:The logs do not themselves detect misissued certificates; they rely instead on interested parties, such as domain owners, to monitor them and take corrective action when a misissue is detected.— RFC 6962 - Certificate Transparency

OK, but what about that undetected MITM attack I’ve been alluding to?

Here’s how that works:

Note that:

- The SCT (signed certificate timestamp) is pretty much irrelevant in this type of attack since the MITM either can order CA/log combos to do what they want, or they own and operate one of the 1200+ CAs out there (in a clandestine operation), or they've hacked their way into obtaining the CA/log private keys they need to conduct mass-surveillance on any website they want (undetected).

- Fraudulent SCTs and SSL certs are generated for target websites and bundled together, sent to victims.

- When the client software requests a Merkle audit proof of inclusion for the cert, it is speaking to the MITM. The MITM in turn, has generated a fraudulent Merkle tree (based off of the legitimate one) that it only shows to the client. Since the client software trusts the public key of the log (which the MITM can use however it likes), the client believes everything is kosher and tells the user: "The connection to this website is secure."

Edit September 28, 2014: The number of CAs out there is disputed, and not all CAs will necessarily have their own log.

#2: Nobody has come up with a way to "effectively revoke self-signed certificates"

There's arguably no point in logging certificates that do not satisfy this criterion, since browsers will not accept them anyway. (It would be nice if the usefulness of self-signed certificates could somehow be bolstered with this kind of log, but the spam problem, coupled with the lack of any way to effectively revoke self-signed certificates, is evidence that no one has found a way to do so; however, see the discussion on other types of logs toward the end of this article.)— Ben Laurie in “Public, verifiable, append-only logs” via ACM.org

It’s been known since at least 2011 that blockchains like Namecoin can do this in a very clean manner, and be done “effectively” using software like DNSChain (mentioned in all but name in 2011).

There is what’s known as a Sybil attack that can prevent blockchain nodes from seeing updates, but this is very hard to exploit and can be detected (see the mitigations in that link). Such an attack would require a MITM to first compromise a specific server’s private keys, and therefore limits the scope of the attack to that server only (whereas in CT, a CA compromise results in MITM for any website on the Internet).

#3: CT is "Generally applicable", a system where "No one is special" and "Everyone must be able to participate."

Everyone can participate. It is not hard to get a certificate into a log, and since the log itself makes no judgment on the correctness of the certificate, there's no change to the revocation of bad certificates, which is still done by the CAs.On the idea that CT logs "[make] no judgement on the correctness of the certificate", Laurie contradicts himself a few paragraphs down and states (as per the RFC) that CT logs do discriminate against self-signed certificates:

Finally, a fourth tradeoff: what should be admitted into a log? An attractive response is "anything," but logs are useful only if their size is manageable. Someone has to watch them, and if they become so large that no one can feasibly do this, then the logs may as well not exist. The straightforward answer is to admit only those certificates that can be chained to a CA that the clients recognize. There's arguably no point in logging certificates that do not satisfy this criterion, since browsers will not accept them anyway.Note that being a CA and running a log is a game that only a few can play. These services are run by an elite group which charges an annual subscription fee for the facade of security (CA-signed HTTPS certificates).

DNSChain & Namecoin, on the other hand, actually don’t discriminate, and they support 100% free self-signed certificates that are actually MITM-proof.

#4: CT doesn't introduce trusted third-parties

No trusted third party is introduced. Although the log is indeed a third party, it is not trusted; anyone can check its correct operation and, if it misbehaves, prove that it did.Saying a thing does not make it true.

As explained in detail above, these logs are being trusted. Those who monitor logs for misbehavior will not see all certificates that have been issued. The reality is that webmasters can be shown “proofs” that mean absolutely nothing. If the webmaster trusts that proof, then he’s trusting the log is not hiding any merkle trees used for the purpose of MITMing users.

There is nothing preventing a rouge CA/log combo (Google itself expects “every major CA” to be a log) from receiving a National Security Letter (NSL) and start MITMing SSL connections with fraudulent SSL certificates that have fraudulent merkle inclusion proofs corresponding to trees that are not shown to anyone else.

The same is true of a CA/log combo that, unbeknownst to the Internet community, is covertly owned and operated by the Five Eyes.

With so many trusted third-parties involved, government spooks aren’t the only ones capable of pulling off these attacks. A group of hackers needs two things to conduct undetected mass-surveillance on millions of netizens: (1) the private keys of one of the 1200+ CAs out there, and (2) access to a “privileged network position” (which can be obtained by hacking into a variety of Internet choke points, such as ISPs).

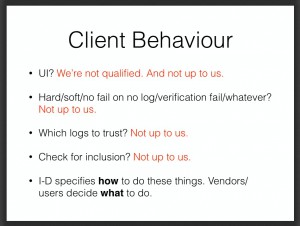

#5: CT doesn't push decisions onto the end user

Finally, Certificate Transparency does not push the decision onto the user. The certificate is either logged or it is not. If it is logged, then the corresponding server operator (or other interested parties) can see it and take appropriate action if it is not valid. If it is not logged, then the browser simply declines to make the connection.At least the following decisions are forced upon "end users" (depending on your definition of "end user" and what decisions browser vendors leave up to users):

- "Server operators" need to constantly monitor these logs and make a decision—"appropriate action"—if they see something wrong. CT doesn't even offer much advice here. Users around the world are supposed to call or email tech support to companies whose languages they don't even speak?

- Clients (browsers vendors & other software) need to figure out what to do in various situations:

- For more, do a case-sensitive search for the words "RECOMMENDED", "MAY", and "OPTIONAL" in RFC 6962.

Response to Laurie's criticism of DNSChain, Bitcoin, & blockchains

Bizarrely, Laurie lists five constraints that solutions should adhere to but does not examine whether the alternatives fit them: (1) possible for Internet to migrate to, (2) scalable & and makes participation possible for everyone, (3) fast, (4) doesn't make things worse, and (5) doesn't force end-users to make decisions.Instead, he dismisses blockchain solutions because:

Bitcoin-based Solutions

I have written extensively on what is wrong with Bitcoin (for example, it is the least green invention ever, and all of its history could be destroyed by a sufficiently powerful adversary if it were truly decentralized, which it is not). Nevertheless, people continue to worship irrationally at the altar of Bitcoin, and this worship extends to DNS and keys—for example, DNSChain (https://github.com/okTurtles/dnschain).Apart from being an extremely costly solution (in terms of wasted energy, in perpetuity), it also introduces new trusted third parties (those who establish the “consensus” in the block chain) and has no mechanism for verification.

OK, so let’s address that.

"history could be destroyed by a sufficiently powerful adversary"

That applies to anything. (Including CT.)"wasted energy"

Blockchains are not responsible for wasting energy:- First off, some blockchains employ consensus algorithms that do not require computation to secure the network. Two of the three existing forks of DNSChain are based on such systems (BitShares DNS and NxtCoin).

- The very concept of "wasted energy" is based on the idea that we have a scarcity of it, which we do not. We have an inexhaustible daily supply of it shining down on us every day, more than enough to power the entire world several hundred times over. It is not the blockchain's fault if humans choose to not use it. Those responsible for "wasting energy" are those who choose to rely on energy sources that can be wasted. Once we stop, you can take month-long steaming showers without any "wasted energy".

- Proof-of-Work can be used to perform calculations that benefit society.

- EDIT March 21, 2015: Even Bitcoin's standard Proof-of-Work consensus mechanism (PoW) does not waste energy. To waste energy is to use it inappropriately or for no purpose. However, PoW uses that energy for a very valuable purpose: securing the blockchain. The result is a decentralized database that has a level of combined security and utility that is literally unprecedented in Internet history.

"introduces new trusted third parties"

This is true, but unlike the thousands of untrustworthy third-parties of CT, users actually have legitimate reason to trust the third party: they know the third party personally and already trust them. The DNSChain server they trust either belongs to them, someone they personally know and trust to operate it, or they can query multiple independent servers and verify the responses match."Has no mechanism for verification"

This is simply not true. DNSChain is the "mechanism for verification". In order to be MITM-proof, its public key fingerprint needs to be verified only once, after which, all other Internet connections (that have their info in a blockchain) become MITM-proof without need for any further verification.There are legitimate issues with blockchains, most notably 51% attacks. On 51% attacks, a lot of interesting research is currently being done, but any distributed and decentralized system will face consensus problems when the majority of participants are malicious. CT, however, makes this problem worse by reducing the number of malicious actors required by orders of magnitude.

The five criteria

Does DNSChain satisfy Laurie's five criteria?- Possible for Internet to migrate to: Yes. The design is much simpler than CT and X.509. The only challenge is wide deployment, but this is possible. Most families run Linux servers at home without realizing they do, and there's not much preventing DNSChain from running on that server. Alternatively, it might even be possible to combine/replace with full-security thin clients running in browsers/OSes (see "Ultimate blockchain compression UTXO", which incidentally employs Merkle trees!).

- Scalable & and makes participation possible for everyone: Yes, as elaborated above, blockchains are far more democratic than today's CA system (and any updates to it, like CT). Successfully decentralized and distributed systems like the blockchain have demonstrably achieved fantastic scalability to date, and that will only improve.

- Fast: Yes. No need to query across the internet to some centralized service to authenticate SSL certs. Just ask your home router.

- Doesn't make things worse: it might lead to loss of profits for Certificate Authorities...

- Doesn't force end-users to make decisions: DNSChain excels at this. No more uncertain hand wringing "proceed with caution" / "make an exception?" SSL warnings. Either the connection is secure or not. The one decision they must currently make (a one-time verification of their DNSChain IP and fingerprint) can be automated in the future to a large extent.

Thank you for reading, and special thanks to Zaki Manian, Simon de la Rouviere, Filipe Beato, and one anon. for reviewing this post prior to publication!

Donating = Loving!

You can empower our work by donating!